Last week I had a party for about forty friends, many of whom didn’t already know each other but most of whom know me through some sort of game or story-related interest. A few others were people I thought didn’t know much about storygaming of any kind, but might enjoy an accessible, casual taster.

So I put together a small narrative game for the occasion. The design goals were to create something that would get people talking to strangers; that would take just a few minutes to participate in, but let people invest more time if they wanted to; that was playable even if you had a plate of food in one hand; that wouldn’t be ruined if some people arrived late or weren’t into playing; and that would produce a souvenir after the party.

The result of this project was San Tilapian Studies.

The Rules:

CALL FOR PAPERS IN SAN TILAPIAN STUDIES

The verdant duchy of San Tilapia once bordered Ruritania in eastern Europe, but it has long since been annexed to larger nations.

For some decades after its annexation, the evidence of its culture was housed in the People’s Museum of Tilapian Decadence, but in time even the museum was razed. The diagrams of its hereditary folk dances, burned. The duchess’ wedding porcelain, smashed.

Scholars in San Tilapian Studies must now make do with fragmentary attestations in letters, diaries, and newspaper reports describing the items that the museum once contained.

But all is not lost! You’re a disciplined and exacting young scholar with tenure to earn. It’s time to piece together the museum’s collection.

THE RULES

COLLECT YOUR EVIDENCE. Take the uppermost slip in the pile of evidence slips. It will bear two fragments of evidence that you have discovered.

Brown stickers represent objects, such as “a loaf of bread”.

Cream stickers represent qualities, such as “very large” or “skeletal”.

Lavender stickers represent functions or effects, such as “ended the war”.COMPARE NOTES WITH OTHER SCHOLARS. In conference with the holders of other evidence, piece together the description of one object you believe used to belong in the museum.

You may find that the first scholars you speak with do not have any information that corresponds well with yours, so feel free to circulate and compare notes until you find a description that resonates with you.

Your team will need one brown, one cream, and one lavender sticker to complete the description, so you will only use one of the two stickers on your evidence slip. In collaboration with others, you will need to decide which of your two stickers contains an accurate description of a genuine artifact and which is a vile forgery.

It is allowed, though of course not required, for your artifact to relate somehow to other artifacts or events already attested in the catalog, if at the time of your research the catalog is already partly filled in.

ADD YOUR REPORT TO THE CATALOG. On a fresh page of the catalog, apply the three stickers describing the item you and your colleagues have rediscovered.

You may also write some sentences of explanation, as well as supplying any sketched images, footnotes, etc. that you feel will help readers understand the significance of the artifact you have reconstructed. We have provided pens and other paper items that may prove relevant, but the best method of interpretation is up to you.

TAKE CREDIT! Sign the names of the team who reconstructed this object.

The Equipment:

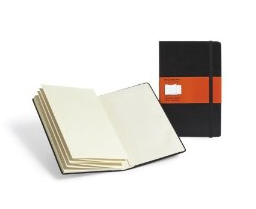

- one Japanese Album Moleskine notebook

(the thickness of the paper and the fact that people could use one or several folds of the book made it easier to prevent accidentally bleeding through onto or crowding someone else’s work)

- 90 custom-printed round stickers, sorted so that two stickers appeared on each slip of backing paper (thus there were 45 slips: 15 bearing a pair of brown “object” stickers, 15 bearing cream “adjective” stickers, and 15 with lavender “function” stickers)

- pens in assorted colors

- four printed copies of the rules

- small selection of paper ephemera such as photos, decorative papers, and postcards loosely themed around early 20th century Europe

- double-sided tape, several rolls, for adding ephemera to the book

The Results:

The finished book contains anecdotes ranging in length from a sentence to several pages, as well as a few other curiosities — a few sketches, a rhymed folk song, and an unsigned entry on a scrap of paper tucked into the back pocket of the notebook. Though I wouldn’t go so far as to say any coherent history emerges, there’s a fairly consistent thematic feel to the thing. Towards the end of the party, people who had particularly enjoyed the exercise started collecting up unused stickers and did a couple extra bonus rounds for fun.

For the most part I feel San Tilapian Studies hit its design goals. It could have been a bit more aggressive in forcing strangers to interact if I’d controlled who wound up with which color of sticker — for instance, it would theoretically have been possible to make sure that all the friends from one friend group got brown stickers and all the friends from another got cream stickers, so they had to talk to one another — but this would have required a much more aggressive administration of the game and I think would not have been especially fun either for the cats or for the person herding them. As it was I just arranged the sticker slips so that they rotated brown-cream-lavender so that there would be an even distribution of people holding relevant slips at any given time.

Also, obviously a lot of the equipment decisions were based around the goal of having a souvenir at the end of it. The same mechanics would have been served using just scraps of paper pinned to a board, for instance, or taped to a big sheet of butcher paper. But I really like having the book as a reminder afterwards, and I feel it would have been a shame to lose the output.

I also had fun making up the sticker set in the first place, via a process of brainstorm-then-cull. I came up with somewhat longer than necessary lists of objects, then ran some random text generation with the different elements and noted which objects, adjectives, etc. seemed to go badly with others a majority of the time. Obviously part of the fun is that not every adjective could sensibly modify every noun, but especially hard-to-match elements were just going to be annoying to people. I also tried to avoid naming specific characters, preferring to allow people to decide who was involved in a given scenario. And of course, the two-items-per-person rule was a final defense against bad assortments; players could ignore something they just thought was too boring or too hard to match up.

I hadn’t realized it was a game of your own design. Well done!

(It was enjoyable.)

Thanks!

I felt the social-engineering part of the exercise was the tricky part; I did my bit relatively early on, when there were a fair number of people wanting to get at the book (and, perhaps, a standard for how much writing was a good amount had yet to be established). Also I just suck at making up stories on the spot, so any design feelings I have about it are probably disguised excuses.

But I ended up feeling as though this might have been ideal for a slightly longer event — possibly a day-long one, involving punch and gentle lawn sports — so people could write in the book several times, when overtaxed by badminton or croquet. Under this system, I would have a straw boater and a very horrible jacket, but my shoes would be exquisite. Your lack of foresight in arranging this version of events can only be deplored.

Curses, straw boaters! I knew there was something I forgot.

I had foreseen the “lots of people want to write” issue, and had intended that, if people wanted, they could write their story on one of the free-floating pieces of paper and then tape it in later. But I didn’t communicate that very well and I think only one or two teams actually used that method to get around the access problem.

Another thing to do might have been to seed the the first page or two with a sample — but, that said, I kind of wanted to just see what people did with it, without interfering by setting up a standard.

I love this idea! Is it under any kind of license? I’d like to study it better to see if it could be adapted to a game I want to make to foster critical thinking in a narrative setting. We’re struggling to find the best medium; IF is too hard for us (none of us are proficient in Inform7), an RPG is a bit too “free” for the objective we have in mind, and we were leaning towards a “choose your path” Varytale-style interactive fiction although we have no idea about how to make one of those. This kind of game could be the most interesting approach to what we have in mind, if it’s at all available.

(BTW: long time fervent admirer since I played “Bronze” and read your examples for the Inform manual)

As far as I understand it, it’s not possible to copyright the mechanics here, so there’s no need for any kind of licensing discussion if you want to write your own rules set and collection of fragmentary data.

If you do want to use my text, though, I’m happy to let people use it under a CC-BY license: do what you want with it, attribute it if you redistribute.

Here’s the set of data we used, though I imagine for other purposes you may want to make your own:

items

a blue diamond

an Italian lace cravat

the photograph of an actress

a nun

a grubby urchin

a nutty Alpine cheese

a disgruntled bullock

a signet ring

two pounds of opium

an official measuring weight

a perfume flask

a funeral urn

Sobranie Balkan cigarettes

the hanged man tarot card

a Baedeker guidebook

a spent bullet

a cavalry officer’s sword

a length of trapeze rope

a ball of clouded crystal

Turkish delight

the collar bearing the name ‘Suki’

a painted gypsy caravan

an antique timepiece

a skull with three eye sockets

a skeleton key

a ten-page letter

a Hungarian newspaper

a hand-carved puppet

a rubied reliquary

a Belgian banknote

qualities

atypically thick

inaccurate in one respect

forged by skilled artisans

unacceptably dull

formerly belonging to a bear

with origins in the antipodes

bigger than a wagon-wheel

decorated with cerulean rosettes

severely water-damaged

stained with ink

covered in fingerprints

nicked by a sword

with a bullet hole through the middle

seen in the fortune teller’s dream

bearing a travel sticker from Morocco

redolent of Tokay

signed across the bottom by a Flemish dignitary

smoldering

heavier than expected

distinctly almond-scented

favored by ladies with aristocratic pretensions

garlanded with white roses

eventually proven fake

smudged with ashes

filled with unsuitable contents

presented in a silver box

painted by a master

fresh from the shop

coated in dust

banned on charges of obscenity

functions

crushed someone

reflected badly on someone

choked public dissent

drained the treasury

provoked a dispute

caused indigestion

deceived someone

revealed the usurper’s name

had to be censored

symbolized the heir-in-exile

secured a crucial alliance

resolved a theological debate

appeased schismatic bishops

represented someone on-stage

figured in folk song

reminded the populace of its grievances

established the identity of a bastard

threatened all the progress so far

revealed someone’s activities

inspired a riot

killed someone

revealed the murderer

placed someone under obligation

foretold the disaster that followed

allowed someone to escape

came between someone and his bride

lured someone out of retirement

turned up under someone’s bed

revived someone’s spirits

caused someone’s capture

Thank you! Yes, I’d adapt the idea and mechanics to a completely new setting and different items, but the idea is to use the same basic idea. It’ll be in Spanish, so the list of items would be quite different too (some things translate well, others, not so much). We’ll see how that works.

Thanks again!

Is this for foreign-language teaching? That adds an interesting layer I hadn’t thought about, if so, since students would need to converse and make sure they understood the text they had. (Though also I suppose adjective-noun agreement might be an issue. Hm.)

No, it’s just that I’m Spanish, and right now I’m in Spain, and I want to use the idea here. Though a simplified version would be great for foreign-language teaching, I think.

Right now I just want to help develop some kind of game that would be a) fun and b) need the use of critical thinking in a narrative context. Sorting out possible alien items on some weird ruins comes to mind. Or determining whether a time-traveler has visited a certain historic location. Something like that. One of the things I had trouble with was which format to use, and this can be a great way to start thinking about things.

Cool.

I don’t know whether this is relevant, but you might be interested — though it’s a longer, higher-investment game than this — in Microscope. Microscope is a rather more rigorous group exercise of historical invention, and it takes more like three or four hours of concentrated play time with a small group; but it’s got various interesting ideas for how to explore the connections between events and so on.

I’ll check it out, it certainly sounds interesting. Thanks again!

Emily, this reminds me of a Spy Party I once crafted in which each guest received a portfolio envelope when they arrived. The goals were similar: Encourage diverse strangers to interact by assigning them roles in which they could playfully develop their character. (I find standard parties dreadfully boring.)

The design criteria were similar: Successful play should not depend on any one character or role who might arrive late or leave early (or never be assigned); Players interactions should be playfully at cross purposes; Alliances were encouraged as well as double-crosses and hidden motives; Players were encouraged to stay in character with enough context created to make this easy; The more fun aspects of a party were worked into the narrative, drink, dancing, and socializing; And lastly, the game could be casually pursued even as one socialized, talked to friends, etc.

The feelies of the game — the portfolio and its contents — were designed so simultaneously give enough clues that guests could easily play the game while never acknowledging that it was game!

For instance, you might arrive at the party to find that you are an ambassador and your mission is to get in contact with an intelligence agent from your embassy who will issue you further instructions.

Or you might be the lover of a Countess who is secretly pumping her for information to turn over to your handler who you are trying to find at the ball.

Or perhaps you are an assassin and your mission is to eliminate the secretary of security and her/his assistant of a foreign power.

We had limited drink tokens that came with the portfolios and these became an unexpected form of currency and people bribed and cajoled each other for information. After someone had been killed, they pinned an elegant square of red felt to their clothing and happily got to drink for free.

Possibilities are quite endless.

Another use of this concept, with a slightly altered premise.